Preface

When the preliminary results in Section D - Endgame Studies of the 11th FIDE World Cup of Composition 2023 were released earlier this week, the biggest surprise for me was the winning study. Here I would like to shed light on this study from several perspectives. I strongly recommend that the reader first study the author's solution and the judge's comments in depth. Both can be found in this PDF file with the preliminary award.

Let's start with another example.

M.A. Zinar

Крымская правда, 1984

White to move and win.

This is one of my favorite pawn endings. In his 1990 book, Zinar gives the solution as follows: 1.Kf2 Kc6 2.Kg2! Kd6 3.Kh3! Kc6 4. Kg4! Kd5

5.Kg3! Kc6 6.Kf4 Kd5 7.Ke3 and wins.

This is an example of so-called cyclic zugzwang, where the same position is reached again with the other side to move. But that's not the point today. Rather, I would like to illustrate with this example that even if you know the solution, the study is not necessarily already understood. Did White really have to go to h3 and why? Are there no alternative maneuvers? It took me some time to be able to answer such questions, but it was a pleasure.

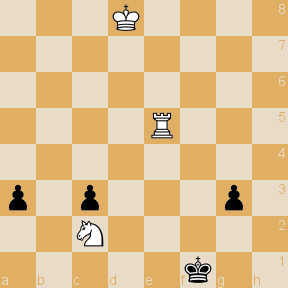

The 1st prize study

1st prize

11the FIDE World Cup 2023

White to move and win.

3+4

The surprise I spoke of above came to me as soon as I took a look at the starting position: 7 men endgame tablebase (EGTB) territory! So something special was to be expected.

After seven moves, six of them with check, the following position is reached.

8. Re7! Logic can be beautiful.

First, let's note that both 8.Nxa3? and

8.Re3? are impossible, since after 8.. g2 White cannot play 9.Ne3. Second, we observe 8. Rg5? g2 9. Ne3+ Ke2 10. Nxg2 c2 11. Rc5 Kd2 or 11. Nf4+ Ke3! and find a significant difference between 8. Re7 and 8.

Rg5?.

Next consider 8. Kd7? as the author did in his second thematic try. Then, because of the text move, 8. Re6? has to be considered, too. This is the author's first thematic try.

At this point we have an idea why the alternatives don't work.

What can Black play in response to 8. Re7! ? He cannot move the a-pawn: 8.. a2 9. Ra7 g2 10. Ne3+ Kf2 11. Nxg2 Kxg2 12. Rxa2+. And after 8.. g2 the game proceeds like in the thematic try after 8.. Re6?, but without the saving double attack at the end. 8.. Kf2 is not mentiond by the author, because 9. Rf7+ would lead to the position which is reached in the mainline one move later. After 8.. Kg2, White can take on a3. So, 8.. Kg1 is the only move left. The ! in the solution is given, because of the extraordinary resistance it puts up. But there is a downside, too. Not so much that the king is in front of the passed pawn, but more important: the king is one square further away from the c-pawn. 9. Rg7! It is this one more square which spoils the line that was possible after 8. Rg5?. 9.. Kf2 10. Rf7+ Ke2 11.Re7+ Kf1. Now we have reached the same position as after 8. Re7!, but it is White to move. In other words, White has won a tempo. This tempo is used to improve the king's position.

12. Ke8! At this point there are a lot of questions. First, the author gives a thematic try starting with 12. Kc8? g2. How is that possible, while g2 does not save the game after 8. Re7 or 12. Ke8 ?

In short: there is one long line, where at the end the c-pawn queens and when the king is on c8, the queen checks and forces White to exchange the knight for the queen resulting in a drawn R vs P endgame. But without the check, the queen can be conquered without material loss.

The other questions are raised by the engines and lead us to another similarity to Zinar's study.

I remember very well the moment I tried to understand Zinar's solution with the help of Stockfish. It showed that at several occasions many white king moves are winning. This is not surprising if you view the study as a complicated triangulation, where usually two or more possibilities exists. Nonetheless some of White's king moves have to be made in the exact order listed. Stockfish wasn't much of a help in this case.

If you ask Stockfish about the position before White's 12 move, it gives a similar answer. There are a lot of winning moves apart of 12. Ke8!, namely

all rook moves on the secenth rank except of 12. Rb7. The EGTB confirms this and the DTZ values

indicate a possible solution: all these rook moves may just be waste of time! I've verified this to a degree, but ultimately I rely on the author and judge.

Although we've only made 12 of the 38 moves, we're almost done. The tempo-gaining maneuver is performed five times by White and the tempos gained are used for

Ke8-f8-g8-h7-g6.

28. Kg6! is called "the crucial point" by the judge, which is a bit exaggerated. Aside from the numerous time-wasting moves, there's still the possibility of going astray with 28.Kh6?. If the game would continue after this move as in the mainline, Black could make a draw with 35.. c1=Q+ because the check wins a tempo. So this case is very similar to the situation after 12.Kc8?.

After 28. Kg6! the white king is so close to Black's g-pawn that it makes no sense for Black to wait any longer with the move g2. The study ends with a sequence of moves that we have already seen with other white king positions. However, these moves are worth seeing until the very end and they definitely crown this work.

Composer opinions

On Wednesday August 9th I posted a GIF on Twitter showing the whole mainline. I added the text "Great?! What do they experts say?" and then I attached the twitter handles of three composers, hoping to get an opinion from them. That worked very well. I received the opinions of five people whom I would like to thank very much. I hope I got the order right.

World champion Steffen Slumstrup Nielsen:

"As mentioned by the judge this is probably a computer product. This is not an issue in itself, but such studies with gradual progress is not my cup of tea. I prefer studies which I can go and show to club players. I want excitement rather than research."

Geir Sune Tallaksen Østmoe:

"It is no secret that my view on that type of studies differs from Steffen’s. To me, it is exciting to research why the baffling Re5-e7!! and the upcoming manoeuvres is

the only way to win. I agree with the judge that it’s a great study."

"I agree. My study got 4th HM and I believe it is better, more human."

My view

The judge of the 11th FIDE World Cup of Composition 2023 is Branislav Djurašević

from Serbia. I would like to thank him specifically for his work. Judging is

probably very difficult and time consuming and in the end not everyone is

happy. Btw, I am 100% satisfied with his assessment of my study (D34).

A study like the first prize is controversial per se. What can a judge

do?

In the World Championship in Composing for Individuals 2019-2021 one particular rule was extended compared to the previous edition:

"In section D, if a study arrives, during the solution, to a position of 7 pieces or less; and especially if it starts with 7 pieces or less, the judge is advised to base his score on his evaluation of the human contribution to the EGTB position, and on the amount of comprehensibility of the study to humans."

That doesn't make the job of a judge any easier. Djurašević has given us insights for his decision which to some extent deals with the above

rule:

"I am aware that without the use of EGTB such a study could not have been composed. But it is our reality to use ordinary computer programs to compose studies for D15, as well as EGTB for D20, are almost the same. Still, the author is like a pilot in an airplane, in charge of deciding which variations are displayed and which are not."

D20 is the 1st prize and D15 the 2nd prize. Unfortunately, the assumption that a chess engine is to D15 what EGTBs are to D20 is wrong. There are at least two major

differences.

The first difference: EGTBs can suggest promising starting positions, chess engines cannot. I think I have to explain that. The most common EGTBs are nowadays known under the name Syzygy. Each material constellation, such as KRN vs KPPP, has two files, and one of them contains distance-to-zero (DTZ) values. Positions with high DTZ values are more promising. The start position of the 1st prize study has a DTZ value of 65. That means, Black can force White to play 33 moves without a pawn move and without a capture. It does not guarantee that there are no duals, of course, but the length of this maneuvering gives good chances that there are long segments without any duals. In the case of this particular study, the mainline is identical to this DTZ path until 28. Kg6, when the study is already close to its end. You might object that most starting positions with high DTZ values are still completely useless. This is where the second difference comes into play.

The second difference is the time needed to get the evaluation of a single

position. This difference is already noticeable when a human operates a chess

engine or an EGTB interface. But it becomes astronomical when certain steps are automated. Let's say your chess engine needs 10

seconds to evaluate a single position. Within this time a program can easily get EGTB information on winning, drawing and losing moves of 20,000

positions. The DTZ values can be used to generate possible mainlines, other forced lines can be detected, possible duals can be added and even tries can be suggested.

You don't even have to be a particular smart programmer to do all this, since access libraries to

Syzygy EGTBs exist for different programming languages and are freely available.

All in all, this means: One can create study-like game fragments in bulk and then find some real studies among them. In particular, neither ideas nor creativity are required.

Does this kill endgame study composing? Or do we have at least to forbid EGTB material? Not at all! The works created with this approach are easy to recognize. Once you understand the approach, you can much better appreciate the human contribution to such a study and thus fulfill the rule cited above. I think, something similar has already happened with zugzwang since files with all zugzwang positions having 3, 4, 5, 6 or even 7 men have been freely available.

And what about the programmers of such algorithms? Do they a devilish work? Well, I can enjoy a study like the 1st prize winner very much. It wonderfully highlights one special aspect of the beauty of chess. And I even really like mining after such miracles and the associated excitement of what I might find next. But when a find triumphs over admirable human studies in a tourney, the programmer in me feels ashamed.